Ultra-Processed Foods and Hormonal Signaling Disruption

- Health

- February 1, 2026

- No Comment

Over the past several decades, food environments have undergone a dramatic transformation. Meals prepared from whole ingredients have steadily given way to industrially formulated products designed for convenience, shelf stability, and hyperpalatability. These products, often described as ultra-processed foods, now make up a substantial share of daily caloric intake in many countries.

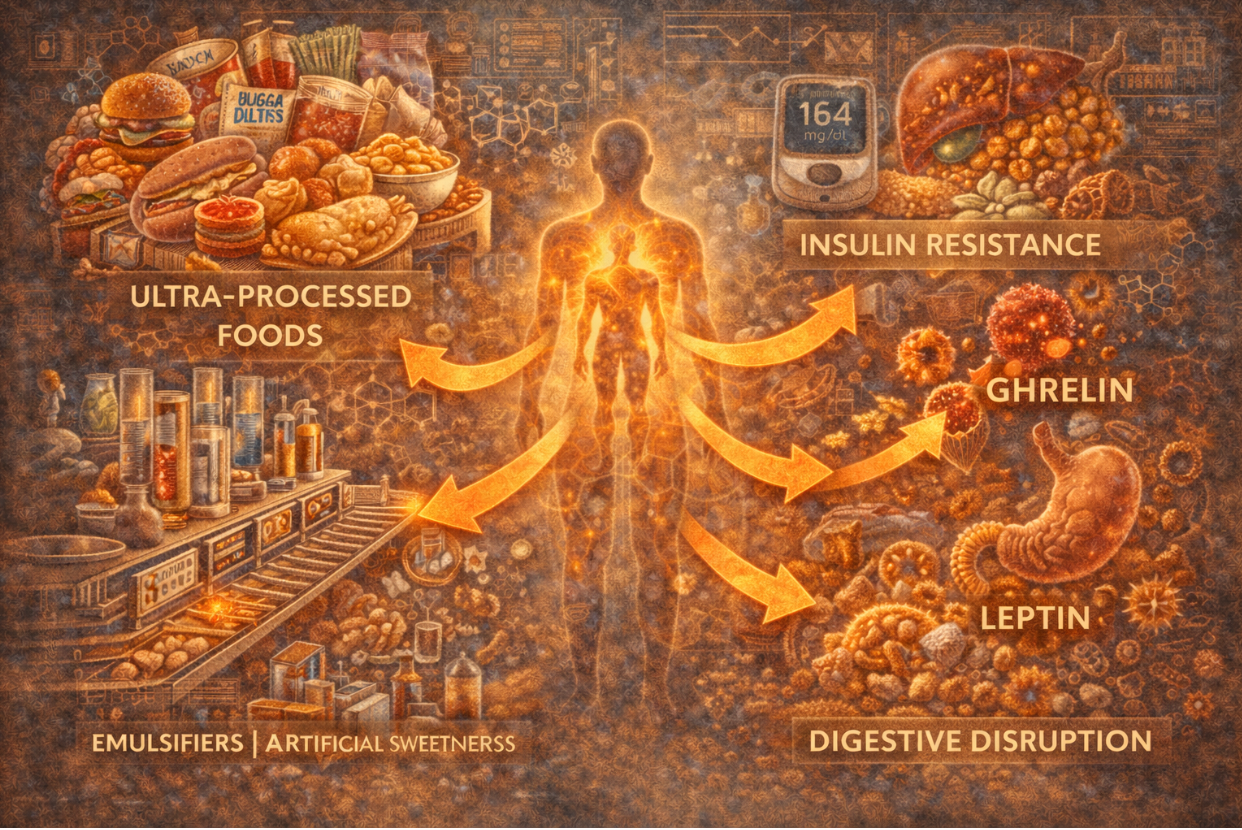

While concerns about ultra-processed foods have traditionally focused on calories, sugar, or fat content, a deeper issue is gaining attention. Increasingly, researchers are examining how these foods interact with the body’s hormonal systems. Rather than acting as neutral sources of energy, ultra-processed foods appear to disrupt signaling pathways that regulate appetite, metabolism, and long-term energy balance. Understanding ultra-processed food effects through the lens of hormonal signaling offers a clearer explanation for why modern dietary patterns are so closely linked to metabolic dysfunction.

Contents

- 1 What Defines Ultra-Processed Foods

- 2 Hormones as Regulators of Eating Behavior

- 3 Insulin Signaling and Rapid Nutrient Delivery

- 4 Leptin Resistance and Satiety Breakdown

- 5 Ghrelin and Appetite Stimulation

- 6 Food Additives and Endocrine Interaction

- 7 Disrupted Gut–Hormone Communication

- 8 Stress Hormones and Dietary Patterns

- 9 Energy Intake Without Energy Regulation

- 10 Long-Term Metabolic Consequences

- 11 Rethinking Diet Quality Beyond Nutrients

- 12 Ultra-Processed Foods as a Signaling Problem

- 13 Implications for Modern Diet Patterns

What Defines Ultra-Processed Foods

Ultra-processed foods are not simply foods that have been cooked or preserved. They are industrial formulations composed largely of refined ingredients, additives, flavor enhancers, emulsifiers, and stabilizers. These products are engineered to be easy to consume, highly palatable, and resistant to spoilage.

Common examples include packaged snacks, sweetened beverages, processed meats, ready-to-eat meals, and many breakfast cereals. Their defining feature is not a single nutrient, but the degree of processing that alters food structure and biological interaction.

This structural alteration matters. Food structure influences digestion speed, hormonal response, and satiety signaling. Ultra-processed foods are designed to bypass many of the natural checks that regulate intake.

Hormones as Regulators of Eating Behavior

Human eating behavior is governed by a complex hormonal network. Hormones such as insulin, leptin, ghrelin, and peptide YY coordinate hunger, satiety, and energy storage. These signals evolved to respond to whole foods that require chewing, digestion, and gradual nutrient absorption.

When these systems function properly, appetite rises when energy is needed and falls when needs are met. Hormonal feedback maintains balance without conscious calorie counting.

Ultra-processed foods disrupt this balance by delivering nutrients in forms that trigger exaggerated or mistimed hormonal responses.

Insulin Signaling and Rapid Nutrient Delivery

One of the most studied ultra-processed food effects involves insulin. Many ultra-processed foods contain refined carbohydrates that are rapidly absorbed, producing sharp increases in blood glucose. The pancreas responds with a surge of insulin to shuttle glucose into cells.

Repeated insulin spikes place stress on insulin signaling pathways. Over time, cells become less responsive, leading to insulin resistance. This state impairs glucose handling and alters how energy is stored, favoring fat accumulation.

Research summarized by the National Institutes of Health shows that diets high in ultra-processed foods are associated with impaired insulin sensitivity and increased metabolic risk.

This disruption is not simply about sugar content. The speed and context of nutrient delivery play a critical role in how insulin signaling adapts.

Leptin Resistance and Satiety Breakdown

Leptin is a hormone that signals long-term energy sufficiency. When fat stores are adequate, leptin communicates to the brain that energy intake can decrease. Ultra-processed foods interfere with this signal.

Highly palatable foods encourage overconsumption, increasing leptin levels. Chronic elevation, however, reduces leptin sensitivity in the brain. As a result, the signal that energy stores are sufficient becomes muted.

This leptin resistance creates a disconnect between actual energy reserves and perceived need. Individuals may continue to feel hungry despite adequate or excess caloric intake.

The breakdown of leptin signaling helps explain why ultra-processed diets are associated with persistent hunger rather than spontaneous intake regulation.

Ghrelin and Appetite Stimulation

Ghrelin, often referred to as the hunger hormone, rises before meals and falls after eating. Whole foods typically suppress ghrelin effectively due to their volume, fiber content, and digestion time.

Ultra-processed foods often fail to suppress ghrelin adequately. Their rapid digestion and low fiber content reduce mechanical and hormonal satiety signals. As a result, ghrelin levels may rebound quickly after consumption, stimulating renewed hunger.

This pattern promotes frequent eating and snacking, reinforcing a cycle of hormonal stimulation that favors overconsumption.

Food Additives and Endocrine Interaction

Beyond macronutrient composition, ultra-processed foods contain additives that may influence hormonal signaling. Emulsifiers, artificial sweeteners, and flavor enhancers interact with gut receptors and microbial populations.

Emerging research suggests that some additives alter gut hormone release and intestinal permeability. These changes can influence systemic inflammation and metabolic signaling.

Studies discussed by Harvard Health Publishing note that ultra-processed foods may affect appetite regulation through mechanisms unrelated to calorie content alone.

While research in this area is ongoing, the cumulative exposure to these compounds raises questions about long-term endocrine effects.

Disrupted Gut–Hormone Communication

The gut is a major endocrine organ. It releases hormones that signal fullness, nutrient status, and metabolic readiness. Ultra-processed foods alter gut hormone dynamics by changing digestion speed and microbial composition.

Highly refined foods reduce stimulation of hormones such as GLP-1 and peptide YY, which promote satiety and insulin sensitivity. At the same time, altered gut microbiota may increase inflammatory signaling that interferes with hormonal communication.

This disruption weakens the feedback loop between consumption and satisfaction, encouraging continued intake even when energy needs are met.

Stress Hormones and Dietary Patterns

Ultra-processed diets are often associated with elevated stress hormones. Rapid glucose fluctuations trigger cortisol release to stabilize blood sugar. Chronic consumption amplifies this stress response.

Elevated cortisol promotes fat storage, particularly in visceral tissue, and further impairs insulin sensitivity. This hormonal environment favors metabolic dysfunction rather than balance.

The relationship between diet and stress hormones highlights how ultra-processed food extends beyond digestion into systemic regulation.

Energy Intake Without Energy Regulation

One of the most striking features of ultra-processed foods is their ability to decouple energy intake from energy regulation. Calories are consumed without activating normal satiety pathways.

This decoupling explains why calorie-based advice often fails in populations consuming high levels of ultra-processed foods. Hormonal signals that would normally adjust intake are overridden by food design.

The result is not simply overeating, but impaired biological feedback.

Long-Term Metabolic Consequences

Over time, repeated hormonal disruption contributes to metabolic conditions such as insulin resistance, fatty liver disease, and obesity. These conditions are often treated as separate diagnoses, yet they share common dietary drivers.

Ultra-processed foods create an endocrine environment characterized by high insulin, blunted leptin signaling, elevated cortisol, and persistent appetite stimulation. This combination accelerates metabolic decline.

Public health analyses published in journals such as The BMJ have linked ultra-processed food consumption to increased risk of cardiometabolic disease and all-cause mortality, independent of calorie intake.

Rethinking Diet Quality Beyond Nutrients

Traditional nutrition advice often emphasizes nutrient targets. Ultra-processed foods complicate this approach because they can be fortified to meet nutrient guidelines while still disrupting hormonal regulation.

This reality has prompted a shift toward evaluating dietary patterns rather than isolated nutrients. Food structure, processing level, and hormonal impact are increasingly recognized as determinants of metabolic health.

Educational resources focused on metabolic and hormonal balance, including those available on Dr. Berg’s blog, often emphasize minimizing consumption of ultra-processed foods to restore natural signaling pathways.

Ultra-Processed Foods as a Signaling Problem

Viewing ultra-processed foods through a hormonal lens reframes their impact. The primary issue is not indulgence or lack of willpower, but biological interference.

When foods repeatedly trigger hormonal responses that promote hunger, storage, and stress, long-term regulation becomes difficult regardless of intention.

This framing helps explain why populations with high ultra-processed food intake experience widespread metabolic issues even when calorie awareness is high.

Implications for Modern Diet Patterns

As ultra-processed foods continue to dominate food systems, understanding their hormonal effects becomes increasingly important. Dietary patterns that rely heavily on these products may unintentionally promote endocrine disruption at scale.

This does not imply that occasional consumption is harmful. Rather, it highlights the cumulative effect of making ultra-processed foods a dietary foundation rather than a supplement.

From a policy and public health perspective, these insights support efforts to emphasize whole, minimally processed foods as the default dietary pattern.

The relationship between ultra-processed foods and hormonal signaling disruption offers a more coherent explanation for modern metabolic challenges than calorie models alone. By altering insulin, leptin, ghrelin, and stress hormone dynamics, these foods reshape how the body interprets energy intake.

Understanding ultra-processed food effects through this biological framework clarifies why dietary change is not simply about eating less, but about restoring the signaling systems that regulate appetite and metabolism.

As nutrition science continues to evolve, hormonal signaling is likely to play a central role in evaluating diet quality. In that context, ultra-processed foods stand out not just as empty calories, but as active disruptors of the body’s regulatory architecture.